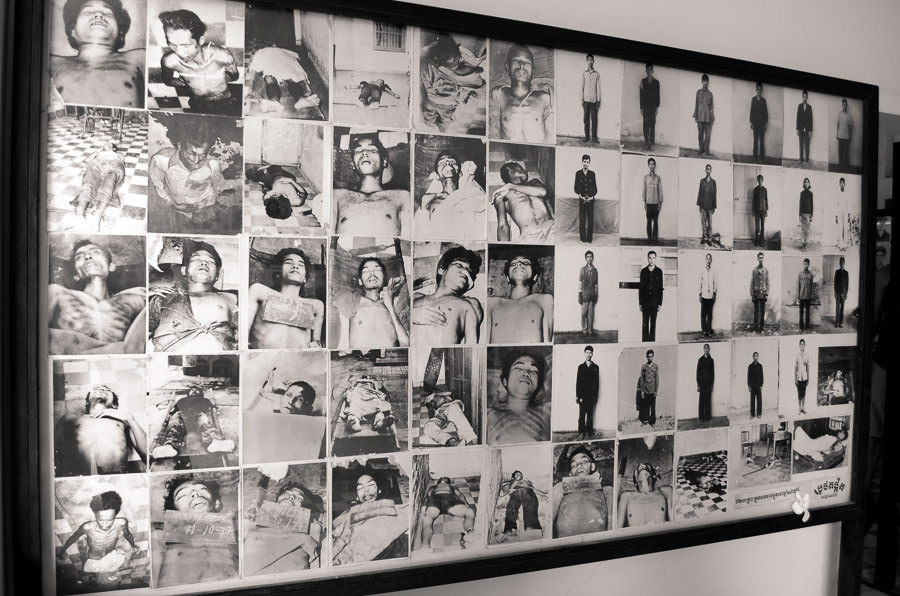

We had already visited the infamous Tuol Sleng Prison in Phnom Penh, gazed at the countless photos of victims displayed in rows and walked through the very killing fields made famous by the Khmer Rouge. But, it wasn’t until reading her story that it really hit me.

Loung Ung, author of First They Killed My Father was five when the Khmer Rouge evacuated her family, and every other resident, out of the capital city of Phnom Penh. They were forced to walk long hours for numerous days in the blazing heat, until they reached a communal camp where the Khmer Rouge soldiers confiscated their belongings, gave them uniforms to wear and served them work orders. As an educated, middle-class family with ties to the government, they were viewed as an enemy and therefore forced to conceal their identities in an attempt to survive. They lived in constant fear of being found out as they would most certainly be killed.

Loung’s father worked tirelessly in the rice fields for fourteen hours a day. Her two older brothers were taken away from the family to work in labor camps. Her oldest sister, just fourteen years old, was also sent away to a teenage work camp but within a few months of arriving there she died of diarrhea that her body was too weak to fight off. The three youngest children were made to work in the garden with their mom and scrounge for food. Living off a few spoonfuls of watery rice soup a day and working like slaves, they were literally starving to death. Malnutrition and its effects were ravaging their bodies leaving them in constant agony.

One day, twenty months into the Khmer Rouge’s nearly four-year reign, two soldiers approached their hut and asked for her father. They said they needed his help with an ox cart that was stuck in the mud and he’ll be back in the morning but it is a lie and they all know the truth – he will never come back. He asks for a moment to speak with his family, takes his wife inside and comes out a few minutes later unaccompanied. He addresses his children one by one, taking them into his arms and kissing them, before turning to walk away, a soldier on each side.

Reading this account of her story, I am there. But, I’m not a young girl watching her father walk away. Instead, I am her mother, only thirty-seven years old and standing, desperate, inside an empty hut as my love is being led to what I know will be a merciless and brutal murder. With the death of my daughter still fresh on my heart, I am burdened with the care of my starving children, without the one thing I knew for sure I could trust. The grief is unimaginable and I wonder how I can continue to live under the crushing weight of this sadness. I am helpless, I am broken, I am alone.

Here in Cambodia, everyone has a story to tell like this one.

We have been here for two weeks now and I’ve learned so many things I never knew before arriving. I’m not sure if I was too busy writing letters to my boyfriend during world history class or if our books just failed to mention the not so long ago genocide in Cambodia. Whatever the case, I was unaware, until now.

Over a four-year span of time (1975-1979) almost two million people were killed in Cambodia through execution, starvation, disease and forced labor, totaling nearly a fourth of the country’s population. That’s like California, Texas and New York being completely wiped off the American map. However, this all occurred in a much more dense area, Cambodia is roughly the size of Missouri.

Here are the basics of what happened, as I understand it. In 1975, when the Khmer Rouge took over, Cambodia was already in a state of unrest. There was a civil war being fought between the government and the army and the war between their neighboring Vietnam and the US was spilling across the borders. Cambodia held a neutral status in the war but allowed the Viet Cong to transport and store weaponry on their land so President Nixon gave secret orders to our National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger saying, I want everything that can fly to go in there and crack the hell out of them.

Between 1969 and 1973 the US dropped 2.7 million tons of explosives on Cambodia whose population at the time was smaller than New York City’s. The number of people killed in the carpet bombings range from the low hundred thousands and go up from there, although exact figures cannot be determined. The bombings that were intended to intimidate the Vietnamese, devastated innocent villages and sent survivors into the city of Phnom Penh to find shelter. This fleeing of the countryside upended the already delicate food supply and overcrowded the city, destabilizing the balance between urban and rural life.

The US bombings also served to radicalized a people who were otherwise indifferent to politics. Their families were killed and their livelihood threatened, they were enraged at whoever was wreaking such havoc on their lives and hungry for revenge.

This is where, Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge gained traction. He created propaganda to spread his communist message throughout the country and rallied people around his crazy ideas. He aimed to rid the country of all western influence and promote an agrarian society where laborers were valued above businessmen and rural life was seen as better than city life. He managed to convince the poor peasants that all their troubles were the fault of the wealthy and in doing so grew his troops with young, angry men. He targeted the most educated and systematically murdered an entire generation of intellectuals, professionals, minorities and ordinary citizens that were unwilling to conform. Anyone who could read or write was seen as impure and killed. The use of money, medicine and education was discontinued and schools were turned into prisons, the most notorious being Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh.

Better known as S-21, this former high school turned prison held approximately 17,000 prisoners throughout the Khmer Rouge rule. Inmates were brought in, photographed then repeatedly tortured and coerced to confess to things like being a cooperative for the CIA, an organization most had never even heard of. After the confessions were recorded prisoners were held in tiny cells until the time came for their execution. Late at night, they would be piled into the back of a truck and driven to Choeung Ek (coined The Killing Fields) a few miles outside the city. With revolutionary music blaring from loud speakers to drown out the screams and florescent lights illuminating the way, people were individually led to mass graves where soldiers bludgeoned them to death (in order to save their expensive bullets) before pushing them onto the pile of corpses below. Some were undoubtedly buried alive.

It’s been thirty-four years since the Vietnamese came in and pushed out the Khmer Rouge regime. Cambodia is still fighting to recover and rebuild while most of the leaders responsible for the damage have died without ever being held to account. As a country riddled with poverty and corruption there is a lot of work to do but the strength and resilience of the people cannot be questioned.

Two weeks ago my knowledge of the Cambodian Genocide was limited to the bits Adrian had shared from his previous trip but I have since received a hands-on education of the history and culture of this nation. The experience has provoked many questions for me, questions that the Cambodian people are currently working out for themselves, namely how do we heal and move on? I hope for them that the answers come sooner rather than later.

*First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remember is available on Amazon.

Pingback: Street Lights : Adrian Landin